10 minute read

Note: when I started writing this post, I didn’t know it would be this long.

I decided then to split it in several posts, each one covering one or more interesting aspect of zsh.

You’re now reading part 1.

I first used a Unix computer in 1992 (it was running SunOS 4.1 if I remember correctly).

I’m using Linux since 1999 (after using VMS throughout the 90s in school, but I left the Unix world while I was working with RAYflect doing 3D stuff on Mac and Windows).

During the time I worked with those various unices (including Irix on a Crimson), I think I’ve used almost every possible shell with various level of pleasure and expertise, including but not limited to:

When my own road crossed ZSH (about 6 years ago), I felt in love with this powerful shell, and it’s now my default shell on my servers, workstations and of course my macbook laptop.

The point of this blog post is to give you an incentive to switch from insert random shell here to zsh and never turn back.

The whole issue with zsh is that the usual random Linux distribution ships with Bash by default (that’s not really, true as GRML ships with zsh, and a good configuration). And Bash does its job well enough and is wide-spread, that people have usually only low incentive to switch to something different. I’ll try to let you see why zsh is worth the little investment.

Which version should I run?

Right now, zsh exists in 2 versions a stable one (4.2.7) and a development one (4.3.9).

I’m of course running the development version (I usually prefer seeing new bugs than old bugs :-))

I recommend using the development version.

UTF-8 support, anyone?

Some people don’t want to switch to zsh because they think zsh doesn’t support UTF-8. That’s plain wrong, if you follow my previous advice which is to run a version greater than 4.3.6, UTF-8 support is there and works really fine.

Completion

One of the best thing in zsh is the TAB completion. It’s certainly the best TAB completion I could use in every shell I tried. It can completes almost anything, from files (of course), to users, including but not limited to hosts, command options, package names, git revisions/branches etc.

Zsh ships with completions for almost every shipped apps on earth. And the beauty is that completion is so much configurable that you can twist it to your own specific taste.

To activate completion on your setup:

% zmodload zsh/complist

% autoload -U compinit && compinit

The completion system is completely configurable. To configure it we use the zstyle command:

zstyle <context> <styles>

</styles></context>

How does it work?

The context defines where the style will apply. The context is a string of ‘:’ separated strings:

‘:completion:function:completer:command:argument:tag’

Some part can be replaced by , so that ‘:completion:’ is the least specific context.

More specific context wins over less specific ones of course.

The various styles selects the options to activate (see below).

If you want to learn more about zsh completion, please read the zsh section completion manual.

Zsh completion is also:

When zsh needs to display completion matches or errors, it uses the format style for doing so.

zstyle ':completion:*' format 'Ouch: %d :-)'

%d will be replaced by the actual text zsh would have been printed if no format style were applied.

You can use the same escape sequences as in zsh prompts.

Since there are many different types of messages, it is possible to restrict to warnings or messages by changing

the tags part of the context:

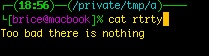

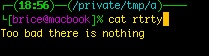

zstyle ':completion:*:warnings' format 'Too bad there is nothing'

And since it is possible to use all the prompt escapes, you can add style to the formats:

# format all messages not formatted in bold prefixed with ----

zstyle ':completion:*' format '%B---- %d%b'

# format descriptions (notice the vt100 escapes)

zstyle ':completion:*:descriptions' format $'%{\e[0;31m%}completing %B%d%b%{\e[0m%}'

# bold and underline normal messages

zstyle ':completion:*:messages' format '%B%U---- %d%u%b'

# format in bold red error messages

zstyle ':completion:*:warnings' format "%B$fg[red]%}---- no match for: $fg[white]%d%b"

And the result:

Grouping completion

By default matches comes in no specific order (or in the order they’ve been found).

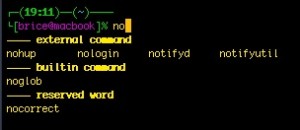

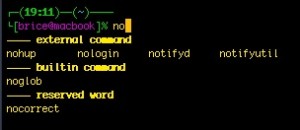

It is possible to separate the matches in distinct related groups:

# let's use the tag name as group name

zstyle ':completion:*' group-name ''

An example of groups:

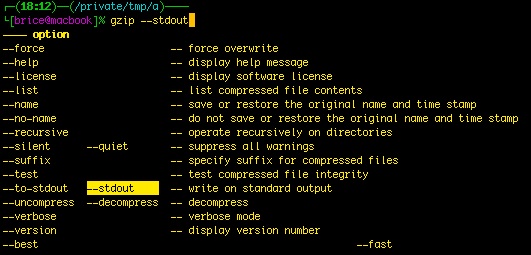

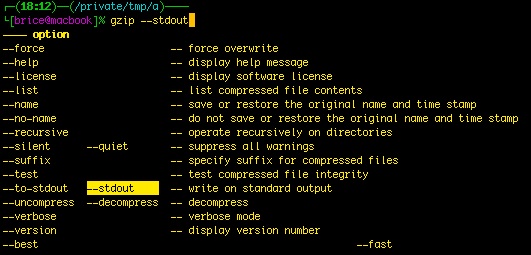

Menu completion is when you press TAB several times and the completion changes to cycle through the available matches. By default in zsh, menu completion activates the second time you press the TAB key (the first one triggered the first completion).

Menu selection is when zsh displays below your prompt the list of possible selections arranged by categories.

A short drawing is always better than thousands words, so hop an example:

In this example I typed gzip -<TAB> then navigated with the arrows to –stdout.

To activate menu selection:

# activate menu selection

zstyle ':completion:*' menu select

There’s also approximate completion

With this, zsh corrects what you already have typed.

Approximate completion is controlled by the

completer.

Approximate completion looks first for matches that differs by one error (configurable) to what you typed.

An error can be either a transposed character, a missing character or an additional character.

If some corrected entries are found they are added as matches, if none are found, the system continues with 2 errors and so on.

Of course, you want it to stop at some level (use the max-errors completion style).

# activate approximate completion, but only after regular completion (_complete)

zstyle ':completion:::::' completer _complete _approximate

# limit to 2 errors

zstyle ':completion:*:approximate:*' max-errors 2

# or to have a better heuristic, by allowing one error per 3 character typed

# zstyle ':completion:*:approximate:*' max-errors 'reply=( $(( ($#PREFIX+$#SUFFIX)/3 )) numeric )'

Completion of about everything

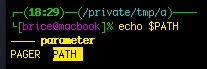

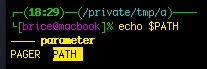

From X windows, to hosts from users, almost everything including shell variables can be completed or menu-selected.

Here I typed “echo $PA<TAB>” and navigated to PATH:

Now, one thing that is extremely useful is completion of hosts:

# let's complete known hosts and hosts from ssh's known_hosts file

basehost="host1.example.com host2.example.com"

hosts=($((

( [ -r .ssh/known_hosts ] && awk '{print $1}' .ssh/known_hosts | tr , '\n');\

echo $basehost; ) | sort -u) )

zstyle ':completion:*' hosts $hosts

Aliases

Yeah, I see, you’re wondering, aliases, pffuuuh, every shell on earth has aliases.

Yes, but does your average shell has global or suffix aliases?

Suffix Aliases

Suffix aliases are aliases that matches the end of the command-line.

Ex:

Now, I just have to write:

And zsh executes nano index.php. Clever isn’t it?

Global Aliases

Global aliases are aliases that match anywhere in the command line.

Typical uses are:

% alias -g G='| grep'

% alias -g WC='| wc -l'

% alias -g TF='| tail -f'

% alias -g DN='/dev/null'

Now, you just have to issue:

to find all firefox processes. Still not convinced?

Too risky?

Some might argue that global aliases are risky because zsh can change your command line behind your back if you need to have let’s say a capital G in there.

Because of this I’m using the GRML way: I use a special key combination (see in an upcoming post about key binding) that auto-completes my aliases directly on the command line, without defining a global alias.

Globbing

One of the best feature, albeit one of the more difficult to master is zsh extended globing.

Globbing is the process of matching several files or paths with an expression. The most usually known forms are * or ?, like: *.c to match every file ending with .c.

Zsh pushes the envelop far away, supporting the following:

Let’s say our current directory contains:

test.c

test.h

test.1

test.2

test.3

a/a.txt

b/1/b.txt

b/2/d.txt

team.txt

term.txt

Wildcard: *

This is the well known wildcard. It matches any amount of characters.

As in:

Wildcard: ?

This matches only one character.

As in:

% echo test.?

test.c test.h

Character classes: […]

This is a character class. It matches any character listed between the braces.

The content can be either single characters:

[abc0123] will match either a,b,c,0,1,2,3

or range of characters:

[a-e] will match from a to e inclusive

or POSIX character classes

[[:space:]] will match only spaces (refer to zshexpn(1) for more information)

The character classes can be negated by a leading ^:

[^abcd] matches only character outside of a,b,c,d

If you need to list - or ], it should be the first character of the class. If you need both list ] first.

Example:

% echo test.[ch]

test.c test.h

Number ranges <x-y>

x and/or y can be omitted to have an open-ended range.

<-> match all numbers.

% echo test.<0-10>

test.1 test.2 test.3

% echo test.<2->

test.2 test.3

Recursive matching: **

You know find(1), but did you know you can do almost everything you need with only zsh?

% echo **/*.txt

a/a.txt b/1/b.txt b/2/d.txt

Alternatives: (a|b)

Matches either a or b. a and b can be any globbing expressions of course.

% echo test.(1|2)

test.1 test.2

% echo test.(c|<1-2>)

test.1 test.2 test.c

Negated matches ^ (only with extended globbing)

There are two possibilities:

leading ^: as in ^*.o which selects every file except those ending with .o

pattern1^pattern2: pattern1 will be matched as a prefix, then anything not matching pattern2 will be selected

% ls te*

test.c test.h team.txt term.txt

% echo te^st.*

team.txt term.txt

If you use the negation in the middle of a path section, the negation only applies to this path part:

% ls /usr/^bin/B*

/usr/lib/BuildFilter /usr/sbin/BootCacheControl

Pattern exceptions (~)

Pattern exceptions are a way to express: “match this pattern, but not this one”.

# let's match all files except .svn dirs

% print -l **/*~*/.svn/* | grep ".svn"

# an nothing prints out, so that worked

It is to be noted that * after the ~ matches a path, not a single directory like the regular wildcard.

Globbing qualifiers

zsh allows to further restrict matches on file meta-data and not only file name, with the globbing qualifiers.

The globbing qualifier is placed in () after the expression:

# match a regular file with (.)

% print -l *(.)

We can restrict by:

- (.): regular files

- (/): directories

- (*): executables

- (@): symbolic links

- (R),(W),(X),(U): file permissions

- (LX),(L+X),(L-X),(LmX): file size, with X in bytes, + for larger than files, - for smaller than files, m

can be modifier for size (k for KiB, m for MiB)

- (mX),(m+X),(m-X): matches file modified “more than X days ago”. A modifier can be used to express X in hours (h), months (M), wweks (W)…

- (u{owner}): a specific file owner

- (f{permission string ala chmod}): a specific file permissions

% ls -al

total 0

drwxr-xr-x 8 brice wheel 272 2009-04-14 18:59 .

drwxrwxrwt 11 root wheel 374 2009-04-14 20:04 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 root wheel 0 2009-04-14 18:59 test.c

-rw-r--r-- 1 brice wheel 10 2009-04-14 18:59 test.h

-rw-r--r-- 1 brice wheel 20 2009-04-12 16:30 old

# match only files we own

% print -l *(U)

test.h

# match only file whose size less than 2 bytes

% print -l *(L-2)

test.c

# match only files older than 2 days

% print -l *(m-2)

old

It is possible to combine and/or negate several qualifiers in the same expressions

# print executable I can read but not write

% echo *(*r^w)

And there’s more, you can change the sort order, add a trailing distinctive character (ala ls -F).

Refer to zshexpn(1) for more information.

What’s next

In the next post, I’ll talk about some other interesting things:

- History

- Prompts

- Configuration, options and startup files

- ZLE: the line editor

- Redirections

- VCS info, and git in your prompt

newcomers, use GRML

But that’s all for the moment.

Newcomer, new switchers, if you want to get bootstrapped in a glimpse, I recommend using the GRML

configuration:

# IMPORTANT: please note that you might override an existing

# configuration file in the current working directory!

wget -O ~/.zshrc http://git.grml.org/f/grml-etc-core/etc/zsh/zshrc